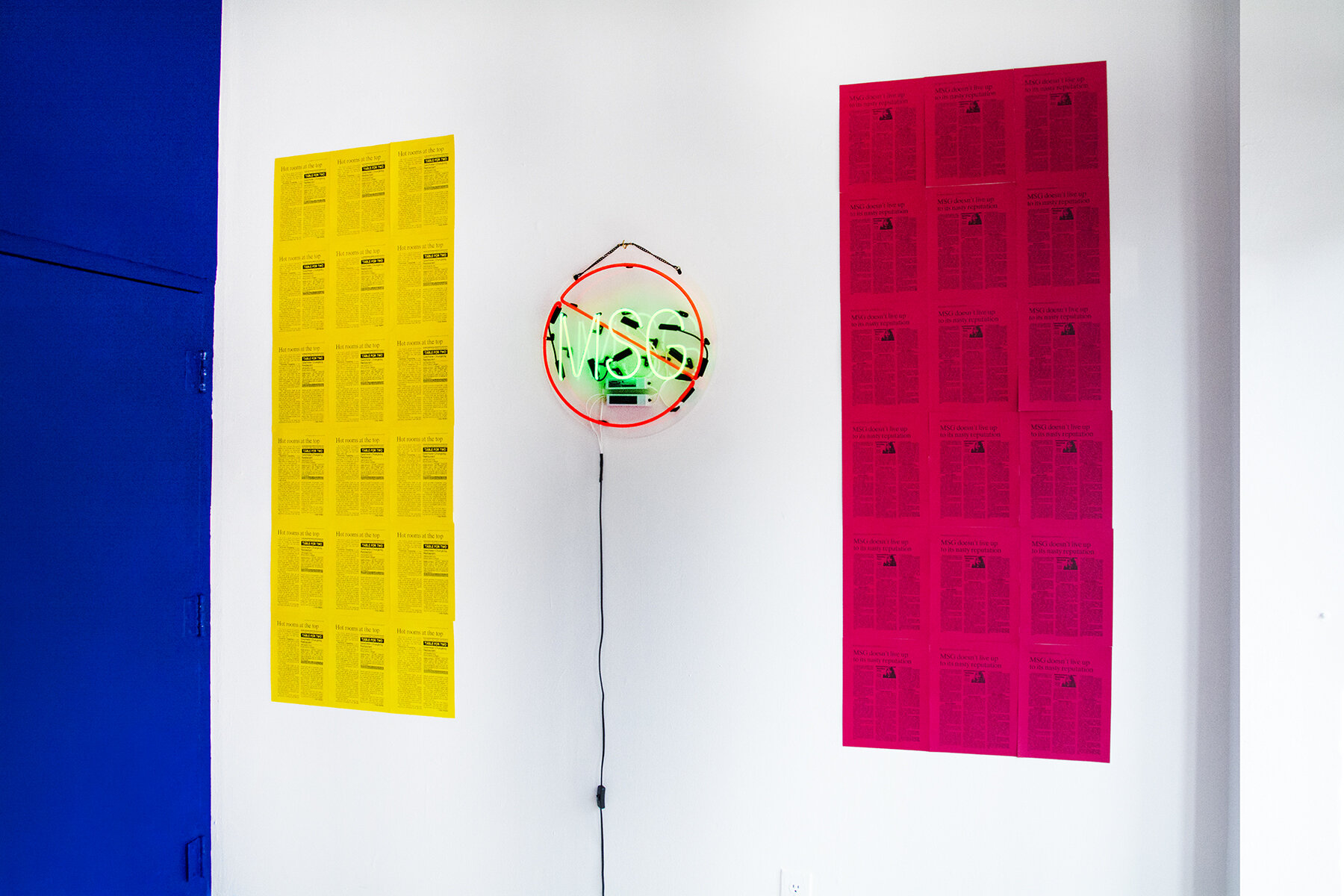

No MSG (In Memory of Lee Garden), 2017

Neon on acrylic

20 x 20”

Ultimately, then, it was no coincidence that Chinese restaurants began to place the now ubiquitous ‘NO MSG’ signs on their menus and in their windows during this period, even while the additive continued to be used widely by American food manufacturers such as Campbell’s, Kraft, Lipton, Knorr and Lawry’s, along with some of the most popular fast food restaurants including Wendy’s, Burger King, McDonalds and Kentucky Fried Chicken.

– Ian Mosby, That Won-Ton Soup Headache’: The Chinese Restaurant Syndrome,

MSG and the Making of American Food, 1968–1980 Social History of Medicine Vol. 22, No. 1 pp. 149

In 1968, the New England Journal of Medicine published a letter to the editor from one reader describing radiating pain in his arms, weakness and heart palpitations after eating at Chinese restaurants. He mused that a combination of cooking wine, MSG or excessive salt might have spurred these reactions. Reader responses poured in with similar complaints, and scientists jumped to research the phenomenon, centring on the glutamic salt, MSG. Not long after, the “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” was born.

When first introduced, MSG was not the antagonized evil that it is often know as today. From the 1930s to late 1960s, MSG was commonly used in North America, often marketed under the brand “Accent” and advised to be used as another seasoning in addition to salt and pepper. As more paranoia came to surround MSG, Western attitudes shifted, assigning the negative connotations of MSG solely on Chinese cuisine. To this day, it is frequently only Chinese and East-Asian restaurants that are forced to attest that they do not use the seasoning in their establishment to assure customers that their business is safe.

Visceral and often communal, food is one of the most accessible ways to engage with a culture. Through its consumption, creation and interpretation, food possesses the unique capability to extend beyond its corporeal restrictions to reflect individual and shared stories, and historical and political climates. Combining a history of product marketing alongside archival materials, Accent presents a case study of the nuanced and racialized undertones within the everyday.

No MSG is a recreation of a neon sign hung from the window of Toronto’s Lee Garden Restaurant. Lee Garden opened in 1978. In 2017, the restaurant suddenly announced it was closing its doors after 39 years.

Fusion Cuisine, No MSG, I Can’t Believe It’s MSG and A Visual History of MSG Marketing are four components of Accent; a project featuring a history of MSG product marketing alongside archival materials from the Toronto Star Newspaper.

Installation photos by Morris Lum.